In our more or less free societies, we regularly see confirmations of an idea well defended by Friedrich Hayek and by Anthony the Jasay. The idea is that remunerations determined by politics, that is, by coercive authorities under the threat of punishment, are not only less efficient but also more conflictual than if determined only by impersonal markets.

In a recent example, the International Longshoremen Association (ILA), a government-protected union (as they all are by labor laws and government bureaus), called a strike. Its leader, Harold Daggett, haughtily threatened 200 million consumers. Of the many employers of his members (container carriers and terminal operators), he said: “We’re going to show these greedy bastards you can’t survive without us!” On their side, the greedy longshoremen are not proletarians: they earn between nearly $100,000 to more than $250,000 a year, much above the average salary in the US (about $60,000). In 2020, 665 dockworkers at the Port of New York and New Jersey were in the more-than-$250,000 category. As a union apparatchik, Daggett himself earns over $900,000 a year; his son, who works for the same unions, earns more than $700,000. ILA temporarily settled the strike for a more than 60% wage increase but still wants to stop automation. This is in a context where the most productive port in America (Charleston) is ranked 53rd in the world. (See “A Ports Strike Shows the Stranglehold One Union Has on Trade,” The Economist, October 2, 2024; “A Dockworkers Walkout Would Close Ports From Maine to Texas and Slam the U.S. Economy,” Wall Street Journal, September 30, 2024; and “The Profane 78-Year-Old Leading the Dockworkers Strike,” Wall Street Journal, October 2, 2024).

Similar phenomena can be observed in all countries where governments or their trade-union proxies exert a direct influence on wages. It extends to public sector unions, who have their hands directly in the public treasury. Consider unions representing employees of the London Underground, the subway system run by a local government body in the UK capital. The secretary general of one of the unions said that the pay offer to its members fell “short of what [they] deserve” (“London Underground Workers to Strike Over Pay,” Financial Times, October 16, 2024). In France, employees of the government’s public transport organizations regularly go on strike for more money and benefits; the strikes are respectfully called “social movements” (mouvements sociaux).

An individual naturally thinks that his value “to society” is not well enough recognized by his fellow humans and especially by his fellow citizens. The phenomenon is analogous to how an individual not familiar with economics thinks the prices he pays for what he buys are too high while the price he receives for his labor services is too low. The complaint takes many forms: I am not fairly remunerated according to my needs, my talents, or what I deserve according to this or that criterion; I don’t get the respect owed to me. Before its members rejected the latest offer from Boeing, which is in deep financial trouble and is cutting 10% of its workforce, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers declared (“Boeing Workers to Vote on Ending Strike in Critical Week for Plane Maker,” Financial Times, October 20, 2024; also “Boeing Factory Workers Reject Latest Contract Offer,” October 24, 2024):

Workers will ultimately decide if this specific proposal is sufficient in meeting their very legitimate needs and goal of achieving respect and fairness at Boeing.

In a free society, with wages and other benefits determined on markets, this temptation is countered by the fact that the determination is not made by an organization. An employee’s bosses may appear to make it, but it is an illusion: the employee is free to move to another employer or to become self-employed; if he doesn’t, it is because he suspects he could not gain more (at constant risk). There is no identifiable authority that underestimates his value. Remuneration is impersonally determined.

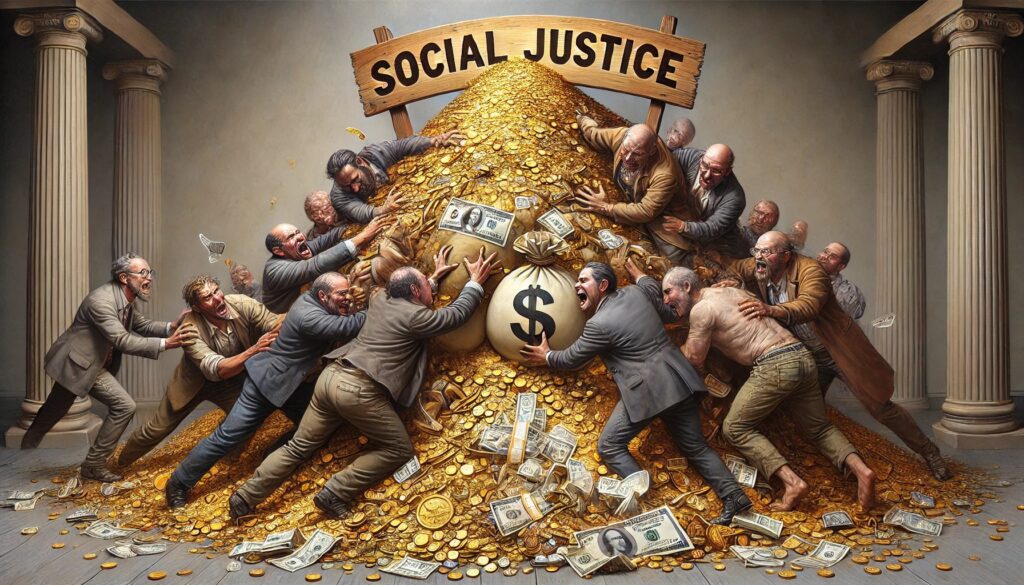

This mechanism does not work when politics determines remuneration. An organization—either a democratic assembly or some strongman—is able to determine by law or diktat the value of your services. The process is typically called “social justice” according to some criteria or other. When it supports richer individuals, the process is called “industrial policy” or something similar. Because everybody thinks he deserves more, the game consists in staking your claims more forcefully to have them politically enforced. The individuals who win are those who are better organized and more politically powerful. In the meantime, the game has changed from impersonal to personal, from voluntary exchange to government commands, from a positive-sum game to zero-sum and eventually negative-sum.

Perhaps one can persuade oneself that the market is more efficient and just than politics with the following thought experiment. Imagine a perfectly democratic system whereby remunerated occupations would be divided into a certain number of categories and an online referendum would be held regularly (every quinquennium or every year or every month or every day) to determine the remuneration to prevail in each category. Would you prefer this system to free agreements on markets?

******************************

The quest for social justce