The idea that the only thing missing in a project is “political will” is a cliché representative of our times. We find it again in a Financial Times article about regulating social media ( “The Coming Battle Between Social Media and the State,” January 21, 2025):

But there are two problems with regulating social media platforms. … The second is that to impose effective regulation against unwilling platforms will require determined, unflinching governmental action and political will

The first meaning of political will is apparent in the vocabulary: “determined” and “unflinching” “governmental action.” Severe laws and regulations must be imposed to control those who don’t want to be controlled. If they don’t submit, their property will be confiscated and they will be fined, jailed, or worse. Ultimately, political will is state violence, threatened or actual. We may call this the raw definition of political will.

A second conception of political will is sugarcoated and more procedural: it is what some politicians or rulers want strongly enough to persuade their colleagues to accept or not reject it as laws or regulations (or extra-legal actions). It does not matter for this understanding of the expression whether the main motivations of state agents are self-interested, as public choice theory safely assumes, or represent an attempt to realize “the social good” or to help or punish this or that group of individuals. Political will in this sense is simply what the rulers can agree on—the output of the rulers’ horse-trading.

An attempt at defining political will was made by Lori Ann Post (a sociologist), Amber N.W. Raile (an expert in “social influence”), and Eric D. Raile (a political scientist), “Defining Political Will,” Policy and Politics 38-4 (2010), pp. 652-676. They quote another researcher observing that political will is “the slippiest concept in the policy lexicon,” and it doesn’t seem they went much further than that, or at least not farther than the horse-trading definition.

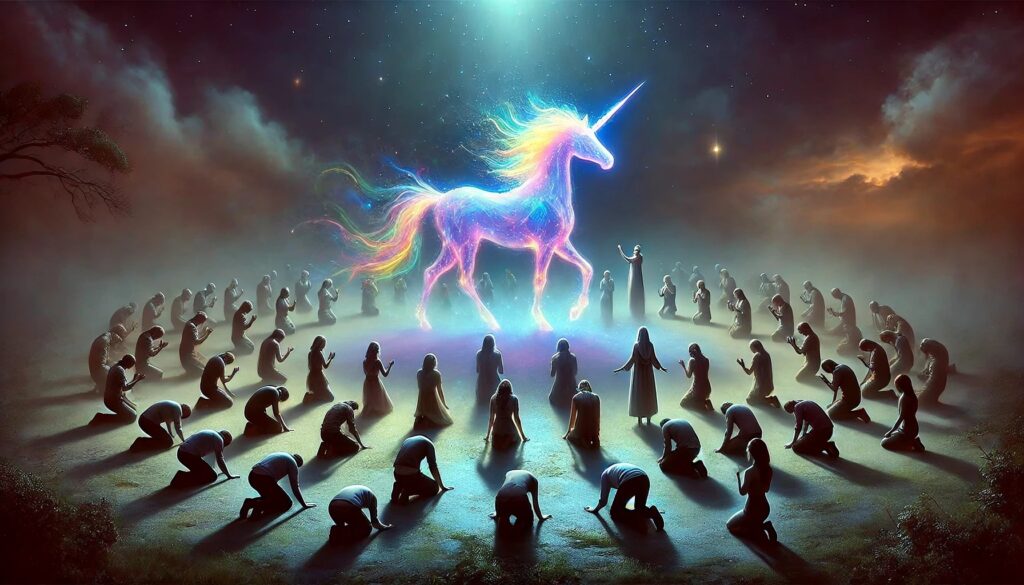

Many people seem to explicitly or implicitly distinguish and elevate a third meaning of the expression, which is focused on the will of the people, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau would call it (The Social Contract, 1762). Except in a mob, the will of the people, if there is such a thing, will not be automatically realized for a host of reasons explained by economics, which may be summarized under the heading of the problem of collective action (see Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action, 1966): everybody wants something but would free-ride if not forced to contribute for his own good. In reality, the will of the people does not exist because there is no homogeneous people—individuals are not identical—and numerical majorities are incoherent (Condorcet paradox and such); it’s a unicorn (see William Riker, Liberalism Against Populism, 1982). The will of the people means nothing but the imposition by state force of the preferences and values of some group, or attributed to some group, on the rest of “the people” and the “enemies of the people,” foreign or domestic (I develop these ideas in my “The Impossibility of Populism,” The Independent Review, 26-1 [Summer 2021], pp. 15-25).

Liberal social contract theories are attempts to reconcile democracy with the fact that “the people” as a distinct being, organic or collective, does not exist. The most sophisticated and economically realistic of such contractarian theories is, I believe, that of James Buchanan and his fellow theorists. In a nutshell, they argue that all individuals agree on a virtual contract establishing minimal rules to govern social life and limit violence and state force in the common interest of all. “The people” in the singular and collective form is not only unnecessary but illusory. The supposed will of the people is replaced by the consent of each and every individual at the “constitutional stage.” The political will, if there is any remaining room for this concept, might be the (suspicious) maneuvering of state agents (politicians and bureaucrats) to help individuals enforce the unanimous rules they agree on or, ominously, to benefit some individuals at the cost of others. It is safer to avoid the expression.

Note that “people” in its plural and usually indefinite form—say, “the weather was nice and people were playing golf”–is not contentious, but these individuals don’t have a political will in the sense the expression is commonly used.

Another definition of political will would be the state’s capacity to provide what I want, which is related to the Princess-Mathilde conception of the state. The concept points to one side of a conflict over resources, and we are not far from the first definition above.

******************************

The People and Its Will