I recently encountered a couple excellent articles discussing productivity problems in English-speaking countries. A paper by Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes and Sam Bowman begins by showing how the UK lags far behind France in building things like housing, expressways, subways, high speed rail lines, nuclear power plants, and other forms of infrastructure.

France and Britain are a particularly interesting pair of countries to examine, because they have so many similarities. Both have a population between 65 and 70 million, and both have roughly the same per capita GDP. (The UK is a bit higher in nominal terms, France is a bit higher in PPP terms.) Both were important colonial powers, both have nuclear weapons, both are countries where a single dominant metro area plays an unusually large role.

But there are also some important differences. France is more than twice as large in terms of land area. France is also marginally more socialist. French workers are more productive, but work fewer hours, leaving total per capita output roughly equal. Here is is SHB:

France is notoriously heavily taxed. Factoring in employer-side taxes in addition to those the employee actually sees, a French company would have to spend €137,822 on wages and employer-side taxes for a worker to earn a nominal salary of €100,000, from which they would take home €61,041. For a British worker to take home the same amount after tax (£52,715, equivalent to €61,041), a British employer would only have to spend €97,765.33 (£84,435.6) on wages and employer-side taxes.

And yet, despite these high taxes, onerous regulations, and powerful unions, French workers are significantly more productive than British ones – closer to Americans than to us. France’s GDP per capita is only about the same as the UK’s because French workers take more time off on holiday and work shorter hours.

What can explain France’s prosperity in spite of its high taxes and high business regulations? France can afford such a large, interventionist state because it does a good job building the things that Britain blocks: housing, infrastructure and energy supply.

Basically, both Britain and France do one thing well and one thing poorly. Britain is relatively (and I emphasize relatively) good at incentivizing people to work. France is relatively good at building capital. Within the EU, both countries are only middle of the pack in terms of per capita GDP.

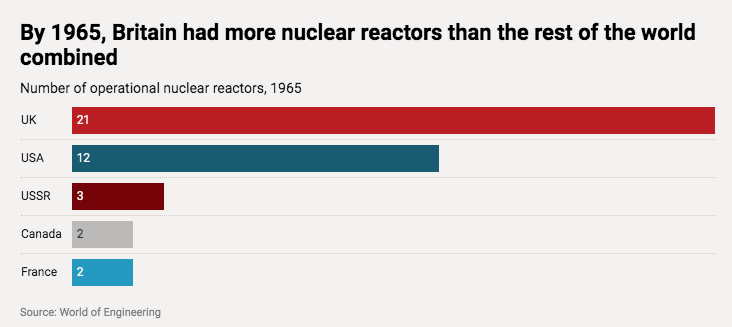

So why is Britain so bad at building things? To begin with, it is recent problem. Britain used to be outstanding at building housing and infrastructure.

It’s a long report, but there are three themes that show up over and over again:

1. Nimbyism

2. Excessive regulation and red tape

3. Inefficient government production

The nimby problem that America experiences in specific places like California and the northeast is a nationwide problem in the UK. And even when projects are approved, Britain has the same sort of excessive regulation of new infrastructure and energy projects that we face in the US, pushing costs much higher. And finally, central governments tend to be more wasteful than local governments or private firms:

French cities pay 50 percent towards nearly all mass transit projects that affect them, and sometimes 100 percent (with regional and national government contributing the rest). Unsurprisingly, they then fight energetically to suppress cost bloat, and they generally succeed. The Madrid Metro, one of the world’s finest systems, was funded entirely by the Madrid region. A smaller and poorer municipality than London succeeded in financing 203 kilometres of metro extensions with 132 stations between 1995 and 2011, about 13 times the length of the contemporary Jubilee Line Extension in London. Other countries still operate systems of private infrastructure delivery: Tokyo’s legendary transit network is delivered, and regularly expanded, by private companies who fund development by speculating on land around stations. France’s superb system of motorways is built and maintained by private companies, who manage them with vigour and financial discipline.

In Britain, the centralisation of infrastructure delivery in the national government has fundamentally weakened this incentive. No public body will ever have quite the existential interest in cost control that a private one does. But national government also has a weaker interest in it than a financially responsible local government does, because the cost is diffused around a vastly larger electorate.

The second article is by Matt Yglesias, and shows how government regulation reduces the effectiveness of the public sector. I suspect that this finding would surprise many people on both the left and the right, who (depending on your point of view) see government regulation as either the government unfairly handicapping the private sector, or preventing abuses in the private sector. Yglesias says they are both wrong, that regulations are much more of a problem for the public sector.

Some parts of the private sector really have become less regulated (airlines), while others have become more strictly regulated (housing), but what’s regulated most strictly of all is the public sector. And this overregulation of the public sector locks us into a vicious cycle. First, we make it very difficult for public center entities to execute their missions. Second, this leads public sector entities to develop a reputation for incompetence. Third, the low social prestige of public sector work leads to the selective exit of more ambitious people. Fourth, elected officials in a hurry to do something often seek ways to bypass existing public sector institutions further reducing prestige.

And what’s actually needed is not more money or more takes about how free markets are out of control or a new anti-growth paradigm.

What we need is a vigorous public sector reform campaign to increase the likelihood that, when elected officials want the government to do X, X occurs in a reasonably timely and cost-effective manner.

Yglesias discusses the way that many counterproductive government regulations only apply to the government sector, not to the private sector. These include well known examples like “Buy America rules” for procurement and Davis-Bacon regulations on labor used by the public sector, but extend to many other lesser known examples of governments shooting themselves in the foot.

It is interesting to compare the British study with the Yglesias post. Both reports seem to be produced by pragmatic policy wonks who would like to see lots more stuff get built. But I would describe Southwood, Hughes and Bowman as center-right, whereas Yglesias is center-left. To be clear, both sides believe that there is an important role for both the public and private sector, but SHB clearly emphasize the advantages of privatization, whereas Yglesias emphasizes how reforms to to make it easier to build can help restore faith in the government’s ability to get useful things done. This may partly reflect differences in the sort of public officials that they are trying to influence.

What I liked best about these two articles is the way they went against long held stereotypes. Ben Southwood has an amusing twitter thread making fun of stereotypes that France is more communitarian than the UK. Yglesias often employs the same type of humor when nudging his readers to think about terms like ‘regulation’ and ‘neoliberalism’ in a less dogmatic fashion, a way that is more consistent with what’s actually going on in the real world.

PS. I suspect that some of the problems discussed in these reports also occur in other Anglosphere countries like Canada and Australia. I hope that commenters from those places will chime in on the subject. Why do English-speaking countries find it so hard to build things? Our legal systems?